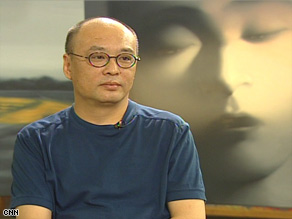

BEIJING, China (CNN) -- AR: Hi I'm Anjali Rao. This week I'm in the Beijing studio of Zhang Xiaogang, a man who's fought his share of battles to become China's leading contemporary artist, and his work now sells for million of dollars around the world. This is Talk Asia.

Chinese contemporary artist Zhang Xiaogang

AR: Putting the finishing touches to his latest work, Zhang Xiaogang is one of China's most famous living artists, with his work exhibited and sold around the world. He broke records last November when his painting "Tiananmen Square" was auctioned for more than 2 million U.S. dollars, making it, at the time, China's most expensive contemporary art. His Bloodline series is also highly prized by collectors. The paintings depict stylized figures drawn from formal family portraits, with distinctive red blood lines illustrating the links between people. A collection of this series dons the metro in Shenzhen. His style, quite simply, is unique.

Vinci Chang: In the past thousand years of Chinese paintings until today, Zhang Xiaogang is one of the most outstanding artists. He actually reveals his feelings and also social, political contexts, and also ideological concerns in China today.

AR: Growing up in southern China during the chaos of Mao's Cultural Revolution, he channels much of his early vision of the world into his work. We catch up with him in a distinctly bohemian area of Beijing, where a number of other artists own studios.

AR: Xiaogang, it's a pleasure to welcome you to this edition of Talk Asia. Now there's so much global demand now for Asian contemporary art, particularly Chinese art. How do you see your role on the world art stage?

ZX: I don't know what contributions I've made. In the world art market today, my situation of that is being at the right place at the right time. After the world has advanced to where it is now, it must choose certain artists. No one person can decide this. I'm just lucky this time period selected me and then allowed me to come into this market and make good progress. For me, it's luck.

AR: As one of China's leading contemporary artists, how much pressure do you yourself feel under to keep producing work that appeals to those who might buy it?

ZX: Because I have been in the art field for some 20 years, it's already become a part of my life. So it was very natural for me to slowly get to where I am today. But all of a sudden the market sped up. For me, the real pressure doesn't even come from the art market. As an artist, the real pressure forever comes from within, from my own expectations of art, as well as an artist's view and understanding of life.

AR: Your works were initially barred from being displayed in galleries here in China. It was seen as not traditional enough and too western, not conventional enough. How did you deal with that?

ZX: My artwork has survived through China's opening-up process over the past 10 years. At first, people didn't really hold contemporary views. Then an acceptance process began. As people began to open up more and faster, people began to accept more modern things. Now people are beginning to learn more and to promote art. I think the whole process is a result of China's increased openness.

AR: Did you at the time see yourself as a rebel? Was it something that you felt insulted by, that they wouldn't show your work?

ZX: The government never said I couldn't display my works, they just said it was a problem of different artistic perspectives. In the past, the government held exhibits of works that reflected a different perspective on life. So for an artist like me, my understanding of art and my understanding of life did not, for example, match the government's exhibition theme, so they wouldn't let me participate in those exhibitions. It was only a difference of ideology rather than other concepts. Ever since I decided to become an artist, I don't think about what others may think about my works. That's the first thing. Secondly, I don't think about trying to create a relationship with the government or anybody else for that matter. All I want to do is to be true to my art. Some may appreciate my work, some might not like my work.

AR: Still, though, looking at your paintings, it seems clear that there is a political element to your work. These days, do you feel that as an artist, you're free to express yourself as you wish in this country?

ZX: Politics play a close role in Chinese people's lives. If you really want to show your perspective on life, your work will naturally reveal a political element. Maybe 10 years ago, works with this kind of political element were not well accepted. But now, with more of China opening up, people have become more open-minded about different perspectives of art. I think this is an improvement.

AR: Your most popular work is the Bloodline series. What's it about?

ZX: It was luck, really. The year was 1993. I was at my parents' house and was looking through their old pictures. That was when I got my inspiration and began thinking about the Bloodline series. I felt that through a family, especially a Chinese family. These old photographs reflected greater society. We all live in one big family. This is different with Western families. Chinese people put a huge emphasis on the family. Family relations include those of blood, those who are your kin, at the same time in society, in your job, you cannot leave these family, like relations. That left a deep impression on me. So I hope that from drawing family photographs, it can reflect my understanding of life. It also incorporates the fact that we live in a society that's very contradictory. I wanted to express this relationship between the individual and society. This kind of relationship is like a son who disobeys his father, yet unable to leave his family behind. It's a complicated relationship.

AR: So this is an example of your famous Bloodline series. Talk me through it.

ZX: This is a couple.

AR: How come their faces look so similar? It's almost like if you took the glasses off and put them on her and cut her hair, she would look like him and vice versa?

ZX: Yes, I wanted to paint them so they look the same. He can be a man or a woman. When people first look at this, it'll look as if they're clones.

AR: So if these two are lovers, how come it looks like they don't even know each other? Have they just had a fight?

ZX: What I care about is not whether or not they are lovers or how their relationship is. I want to show that they are like cloned people and they have the same thoughts. I wanted to make them look as if they were daydreaming.

AR: So I understand obviously what this is, being the Bloodline paintings. What about these little patches of color though on parts of their faces, the one up there above the eye and one down here on the chin?

ZX: Like this one, I use the patches of color on each person's face. It's like a light hitting the person's face, and slowly it becomes a scar that time leaves behind.

AR: Why doesn't anybody in your paintings smile?

ZX: I drew a person smiling once, but I don't think I am good at drawing people smiling. I'm better at drawing people spacing out.

AR: What's happening in this painting?

ZX: I wanted to draw a big landscape that has something to do with water.

AR: What's the significance of the baby then?

ZX: I specifically wanted to draw a baby. It doesn't have anything to do with the landscape. It's like a scene you see in your dream. There's somewhat of a strange feeling.

AR: Yeah, a little bit.

ZX: I have to paint this piece slowly, because I have to express it in layers. It takes a long time.

AR: Talk me through your work day. What does it involve?

ZX: Every day I sleep in the morning. I wake up at noon, eat lunch and then work here in the afternoon until night. And then at night I eat and drink and have fun with my friends.

AR: When you're painting, what sort of things do you need around you? I know that you like to listen to music when you're doing this. But do you work better when there is no one here?

ZX: When there's too many people, there's no way I can paint. So of course, I work alone. As I work alone, when I come to the studio, I put the stereo down. I prepare my tea and water and then turn on some music.

AR: What do you like to listen to, and what do you drink?

ZX: In terms of music, I listen to all sorts of genres. Sometimes I like listening to classical music, sometimes rock, and sometimes ethnic music.

AR: What are you listening to at the moment?

ZX: Right now I'm listening to old music again, such as Pink Floyd.

AR: What do you drink?

ZX: During work, I can't drink alcohol. I can only drink tea. After work, at night, I can drink whiskey.

AR: And does that help with the creative thought process?

ZX: Drinking alcohol can help me relax and change my mood. Otherwise if I just work every day, I'd go crazy.

AR: Do you have an idea in your head before you start painting or do you just sort of put your brush on the canvas and wait to see where it takes you?

ZX: I'll first come up with an idea, and then I'll draw a small sketch. Then I can see how I want to proceed. This thinking process takes a few days. I'll think in front of a blank piece of canvas. If I'm not done thinking yet, then I won't start anything. If I am done thinking and know what I want to do, then I might not stop painting until I finish.

AR: Art is supposed to be a visual representation of history or society. What does your work say about the world in which we live?

ZX: My work mainly reflects my childhood and teenage memories. During the time when I grew up, China was a completely different place from today. My paintings strive to capture a person's process of growing up and the experiences they go through, as well as how they are influenced by the time period in which they lived.

AR: Xiaogang, you grew up during the Cultural Revolution. Tell us what that time was like for you.

ZX: When the Cultural Revolution started, I was eight years old. I was in second grade in primary school. The Cultural Revolution gave me the impression that it was very fun, because I didn't have to go to school. I could always be with my friends and I could see things that a boy my age would want to see, such as weapons and people walking freely along the streets. It wasn't until I grew up that someone told me that period was the Cultural Revolution. It was a horrible time period. There were many problems. But at the time, I thought it was a fun few years.

AR: What made you decide that this was what you wanted to make your living out of?

ZX: From early on, my parents worried that I would go out and get into trouble. So they gave us paper and crayons so we could draw at home. The first teacher was my mother. She taught me how to draw simple things. Slowly, I never stopped. I gained more and more interest in art. I had a lot of time, because I didn't have to go to school. My interest increased. After I became an adult, I never gave up art. So that's how I started to draw. When I was 17, I told myself I wanted to be an artist. So I found a professional teacher. From my teacher, I began to learn how to draw professionally. I felt that art was like a drug. Once you are addicted, you can't get rid of it.

AR: During your professional life though, things haven't always been easy for you. There was a prolonged space of time there where you struggled with depression and also alcoholism. Tell us what those dark times were like for you.

ZX: When I first began my career as an artist, I really didn't think about those things. I worried about learning the principles of art and becoming a professional. Slowly I began to learn more about the philosophy of art, especially through art books, I slowly began to link the art philosophy to my own philosophy. This was a huge change for me. So when I realized this, I tried to find the kind of art that would match my personality and character. I tried to express my character through art and it became a direction I pursued in art.

Different lifestyles, life experiences and surroundings leave different impressions in a person's heart. I think art should be used to express what is in a person's heart. So I pursued this direction to find my own voice through art. Chinese people have experienced too much change, which dramatically influences people internally. I say this from my experience, because I have lived through three completely different time periods in China in a short amount of time. I think art is a resource that we should use to reflect on Chinese people's attitudes towards this fast-paced change.

AR: You might imagine though, that when somebody suddenly gets a lot of success thrown upon them and certainly in a financial sense, that it might prompt a sense of arrogance. You seem completely the opposite, very assuming, and you put down a lot of what you've achieved to luck. How do you stay like that?

ZX: I think this has proven one thing, and that is there are many people who can understand true art. The happiest thing for me is not how much my paintings have sold or how high my artwork is valued. The happiest thing for me is that through the art world, I have met many friends and have been able to find many people who understand me. I don't feel as lonely. This is what makes me most happy.

AR: So Xiaogang, what's happening in this painting?

ZX: This is a school, a small school. This was when I was in Lung Chuan for two years. I remember the area and the loud speakers. I took away all the color in the painting and only highlighted the school in yellow. It's like a dreamlike memory, a picture of a dream.

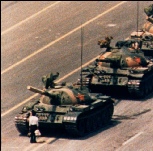

AR: It reminds me a little bit of your work Tiananmen, which sold for more than 2 million U.S. dollars again. And that was obviously supposedly criticizing the massacre that took place there in 1989? Do you see yourself as something of a dissident?

ZX: You can't really say I'm a dissident. I paint meaningful public places, like the school and like Tiananmen. It's supposed to show the relationship we as individuals have with these places.

AR: So Tiananmen was only because it was a public place, not because you were trying to say something, to send a message to the authorities?

ZX: My Tiananmen painting doesn't have anything to do with the incident. Actually when I paint Tiananmen, it's the same as painting a school or painting an ink bottle or a light bulb, in my heart the feeling is the same. I just hope to express myself through art.

AR: Well let's move on to this one. I have to tell you that this is my favorite of all of them. Who is this?

ZX: This is not necessarily about who it is. What I'm trying to capture here is a person's current emotional state to my understanding. It's like a dream.

AR: Yeah, a lot of your work is extremely dreamlike, but another thing that I think obviously is abundantly clear on your work, they all have these patches of one color, like that across a black-and-white background. Explain that to us. What's your interpretation of that?

ZX: I take away most of the color in my paintings, because I want my paintings to be a memory of a person or of a scene, and not what we see with the naked eye with all this color. It's a memory or a realization of something. I add the patch of color to make the painting look more like a dream.

AR: You were mentioning trying to convey an emotion through your works such as this one. What emotion are you trying to display here?

ZX: This painting is supposed to convey a feeling of memory loss and of having memory. It's a contradictory feeling.

AR: Interesting. Ok, well, let's move on to this one over here. See, this one seems more obvious.

ZX: This one is also a work about amnesia versus remembering. I haven't finished this piece yet.

AR: This looks like somebody's struggling to come up with an idea to put on the paper. Is that something that you ever struggle with?

ZX: These are materials I've used before, such as this light bulb. It was how my life was originally. At night when I didn't have a TV, I would write letters or write in my diary to pass the time. It's a very isolated lifestyle.

AR: Yes it must be, I was wondering that before. Do you ever get lonely, because it is such a solitary thing?

ZX: Of course it's lonely. It's just me working by myself. Unlike your job, with all these people having fun, this is a lonely career.

AR: So I'm glad we were able to entertain you. Let's move on. So when people come to your studio, do people just walk in and say, "I'm going to have that one. I'm going to take that one away with me today."

ZX: A lot of people.

AR: Wow. So how much would this one sell for?

ZX: This one is my own. I'm not selling it.

AR: Oh, what a shame.

ZX: Because I personally like this one a lot.

AR: I know it is fantastic, it's beautiful. So this is supposed to be a sort of a farm scape?

ZX: Yes, it's a newly opened piece of land.

AR: Right. Somewhere that you've been? You've painting from experience here?

ZX: No, this is my understanding of the surrounding. It's not a place that I've actually seen. Because in the past, this kind of scenery in China -- a tractor and the red flag -- symbolizes the beginning of a new era. So I tried to draw out that feeling.

AR: Now something that I've really noticed in your works is that a lot of them, when you paint landscapes, is that they've either got something like a flagpole like that or a loud speaker, something that's standing on a high pole. What's that about?

ZX: It looks good.

AR: Do you think people generally understand what you're trying to say in your paintings?

ZX: I think most people can understand. Art is not science. It doesn't have to be accurate. Art is a feeling, a state of mind. That's the most important thing.

AR: There has been a lot of talk, Xiaogang, about that this contemporary art market being a flush in the pan, a bubble that will eventually have to burst. What do you think about that? Would you agree?

ZX: Chinese art had never really entered into the market before. In the past few years, people, in a short amount of time, have tried to test out the market. For Chinese art and for artists, this is a challenge. We have to get through this stage. When we were young, art was just for leisure. I understand the market can benefit some people. At another time, it may have a different target, and then other artists may benefit more. So everything about the market now has to be learned.

AR: Xiaogang, thank you so much indeed for sharing your time with us today and showing us around your beautiful studio. Many thanks indeed. My guest today has been the acclaimed Chinese artist, Zhang Xiaogang. I'm Anjali Rao. I'll see you again soon. Take care.

Le Temps.ch

La révolution occultée

Il y a 40 ans, la Révolution culturelle provoquait des millions de morts en Chine. Figure des gardes rouges, Nie Yuanzi témoigne ici, alors que le pouvoir impose une amnésie nationale sur l'événement.

Titre: Vie et mort de la Révolution culturelle

Auteur: Fernand Gigon

Editeur: Flammarion

Autres informations: 1969

Frédéric Koller, Samedi 3 juin 2006

Esprit clair, destin trouble, Nie Yuanzi est un fantôme de 85 ans que le régime chinois n'a nulle envie de voir ressurgir de son placard. Privée de liberté durant seize ans (camps de rééducation et prison), la «maîtresse des gardes rouges» survit depuis vingt-deux ans grâce à l'aide d'amis dans une pièce unique d'un immeuble décrépi du nord de Pékin avec ses deux chats persans et un téléphone portable qui la relie au monde.

Il fut un temps où la simple évocation de son nom provoquait la ferveur ou la terreur. Aujourd'hui, Pékin l'a effacé des tables de l'histoire comme les «dix années de catastrophes» de la Révolution culturelle dont le 40e anniversaire a été salué par un fracassant silence en Chine. Pas une ligne dans les médias, pas un mot dans la bouche des dirigeants pour évoquer un drame dont les conséquences psychologiques sont une clé essentielle à la compréhension de la Chine actuelle, alors que les postes à responsabilité politique ou économique sont désormais occupés par d'anciens gardes rouges.

Le 16 mai 1966, un éditorial du Quotidien du Peuple appelait à lutter contre le «révisionnisme bourgeois», une attaque codée contre les ennemis de Mao Tsé-toung, dieu de la «Chine nouvelle» dont l'autorité était contestée depuis le désastre du Grand Bond en avant qui s'acheva par une famine ayant entraîné la mort de 30 millions de personnes. Le 25 mai, Nie Yuanzi, qui est alors la secrétaire du Parti communiste du Département de philosophie de l'Université de Pékin, rédige avec six autres camarades le «premier dazibao marxiste-léniniste» appelant les étudiants à se rebeller contre leurs professeurs et à défendre le président Mao.

Le 1er juin 1966, la radio nationale diffuse le texte de l'affiche à grands caractères qualifié par Mao de «déclaration encore plus belle que celle de la Commune de Paris». «Avec une telle caution, écrira plus tard le grand reporter jurassien Fernand Gigon*, cette homélie à la sauce chinoise est devenue l'un des textes sacrés de la Révolution culturelle. [...] Nie Yuanzi changea certainement, par son action, l'équilibre des masses, qui pencheront dès lors du côté de Mao.» Aussitôt, les écoles du pays s'enflamment, puis les usines, enfin toute la société est prise de convulsions qui dégénéreront en une guerre civile qui fit des millions de victimes, seule l'intervention de l'armée permettant d'y mettre un terme.

«A l'époque, se souvient Nie Yuanzi, je pensais simplement qu'il fallait être loyal envers Mao. Je n'aurais jamais pensé que cela provoquerait de tels désastres.» Comme des millions de gardes rouges, le «petit général de la révolution» n'était qu'un pion d'un jeu politique qui la dépassait. Mais un pion si actif qu'il s'attira une haine tenace de Deng Xiaoping (principale victime politique de la Révolution culturelle avec Liu Shaoqi).

La leader des rebelles affirme pourtant qu'elle fut aussi une victime. Accusée dès 1967 par Jiang Qing (femme de Mao) et Lin Biao (successeur désigné de Mao et compilateur du Petit Livre rouge) d'être trop timorée, elle sera enfermée en octobre 1968 alors que le Grand Timonier ordonne le retour à l'ordre une fois ses ennemis au sein du parti éliminés. «Je ne regrette rien, explique la vieille dame qui a écrit l'an dernier à Hu Jintao pour enfin bénéficier d'une retraite. Il faut tirer les conclusions de l'histoire. La Révolution culturelle fut une calamité, l'Etat était en faillite. Mais il y avait des raisons positives à la lancer: lutter contre la restauration capitaliste, c'était combattre la corruption, défendre la démocratie.» Du moins le croyait-elle.

Le destin de Nie Yuanzi est à l'image de tout un peuple. «C'est un personnage tragique, explique Xu Youyu, intellectuel libéral spécialiste de cette période. Elle a été utilisée par Mao qui en a fait ensuite un bouc émissaire. Quarante ans plus tard, elle n'a aucune connaissance des causes véritables de cette tragédie, aucune analyse, aucune réflexion.» C'est ainsi qu'en Chine, aujourd'hui, les personnes qui ont vécu la Révolution culturelle se taisent, alors que les plus jeunes générations méconnaissent ces temps troublés. «Les étudiants des cours politiques de l'école centrale du Parti communiste ne savent rien de cette période, explique un professeur qui préfère garder l'anonymat. Ils ignorent jusqu'au nom de Hua Guofeng (ndlr: successeur désigné par Mao Tsé-toung, qui sera à son tour éliminé en 1978)!»

La grand-mère concède qu'elle a été manipulée par Mao, mais conserve à son égard un jugement équilibré: «Succès remarquables; crimes abominables.» Par contre, elle est amère envers le parti qui l'a rejetée de ses rangs. «La plupart des anciens gardes rouges occupent aujourd'hui des postes importants. Ils n'ont jamais été inquiétés. Personne au Comité central ne s'est opposé à la Révolution culturelle en 1966. Ce n'est pas objectif de faire endosser la responsabilité de ce désastre à la seule «Bande des quatre» comme l'a décidé le parti en 1980.»

Cette responsabilité collective, Nie Yuanzi l'évoque dans un livre de Mémoires publié l'an dernier à Hongkong mais interdit en Chine. Dans une société de plus en plus divisée, le régime converti au capitalisme est moins que jamais disposé à écouter la voix de ses fantômes.

L'oubli, une stratégie de survie

Zhang Xiaogang, peintre auréolé, s'inspire de la Révolution culturelle.

En 1966, Zhang Xiaogang avait 8 ans. Sa Révolution culturelle se résume en deux mots: «amusant» et «sombre». Amusant? «Imaginez, du jour au lendemain, il n'y eut plus d'école. On était laissé à nous-mêmes. Complètement libres. On entendait des coups de fusil. Alors, on jouait à la guerre.» Sombre: «Puis un jour, les gardes rouges ont frappé à notre porte. Mes parents ont été critiqués, nos livres brûlés. Mon père a barricadé les portes et les fenêtres. Il n'y avait plus de lumière.»

En mars dernier, Zhang Xiaogang a atteint le firmament de la peinture contemporaine chinoise. Lors d'une vente aux enchères de Sotheby's à New York, l'un de ses Camarades a frisé le million de dollars, record absolu pour une œuvre d'un artiste chinois vivant du continent. Dans son atelier de la Distillerie - le dernier quartier branché des artistes accolé à une cité de classes moyennes - l'homme garde la tête froide: «Je peins bien, j'ai de la chance et j'ai un bon intermédiaire. C'est tout.»

Les personnages de Zhang Xiaogang - contours flous, yeux embués, reliés par un fil rouge - sont issus de la Révolution culturelle, inspirés par des photographies redécouvertes lors d'une réunion de famille au début des années 1990. Leurs regards perdus évoquent des morts-vivants pétrifiés dans un temps suspendu avec l'oubli pour prison. Un peintre engagé, Zhang Xiaogang? «La politique ne m'intéresse pas, il n'y a aucune réflexion historique ou idéologique. Je ne cherche pas à comprendre la source de ce désordre ni à juger si c'était bien ou mauvais. Je peins simplement un sentiment.»

Un discours calibré par la censure dans un régime où tout, en définitive, relève du politique. Mais une censure intégrée, subtile, qui ne nécessite plus la force. Une grande partie des artistes chinois se réfère aujourd'hui à la Révolution culturelle ou plus généralement au maoïsme dans un mélange ambigu d'ironie (distanciation) et de nostalgie (fascination). «C'était une époque très particulière, très idéaliste, dit Zhang Xiaogang. On n'avait pas besoin de penser. Mao pensait pour nous. C'était une époque d'innovation culturelle influencée par la Russie, d'un art collectiviste. C'était une époque de douleur et d'énergie.»

Zhang Xiaogang n'en dissèque pas moins l'aliénation d'un peuple coupé de ses racines. L'oubli et la mémoire, c'est l'essence de sa démarche artistique. A l'écouter, la référence à la Révolution culturelle n'est qu'un prétexte, presque un hasard. «L'oubli est la base de la philosophie des Chinois. Si l'on veut vivre, il faut être capable d'oublier. En réalité, les Chinois sont très forts. Ils s'appuient sur leur mémoire pour défendre leurs principes et oublient leur passé pour faire face à la situation actuelle. La Chine connaît de tels bouleversements, de telles contradictions, qu'il faut sans cesse s'adapter aux situations nouvelles.»

Force ou faiblesse? Zhang Xiaogang aurait pu ajouter que cet oubli et cette mémoire sont largement dictés par une stratégie de contrôle des esprits dans une logique de préservation du pouvoir des élites dirigeantes. Il ne le dit pas car il réfléchit en référence à un cadre culturel qui serait propre à la Chine. C'est peut-être ce qui l'empêche de raisonner - à l'image de tout un peuple - sur les causes et les fins des soubresauts de l'histoire chinoise. L'esprit des gardes rouges n'est pas si éloigné. C'est aussi ce que nous rappellent les Camarades de Zhang Xiaogang. Malgré lui.

Chronologie

1er octobre 1949: Fondation de la République populaire de Chine.

Mai 1958: Début du Grand Bond en avant. Création des communes populaires.

1961: Fin du Grand Bond en avant, Mao est critiqué par les instances du parti.

Mai 1966: Début de la grande révolution culturelle prolétarienne.

Août 1966: Mao lance son slogan: «Bombardez les quartiers généraux» et convoque la jeunesse à Pékin.

Juillet 1968: Prise du pouvoir par l'armée dans les usines et les universités.

A partir de décembre 1968: Envoi à la campagne d'intellectuels et de jeunes des villes.

1969: IXe Congrès du PCC. Mao est réélu président du Parti et Lin Biao, ministre de la Défense, est nommé son successeur.

Septembre 1971: Elimination et mort de Lin Biao.

Août 1973: Réhabilitation de Deng Xiaoping.

Septembre 1976: Mort de Mao Tsé-toung.

Octobre 1976: Arrestation de la «Bande des quatre», nom donné a posteriori aux quatre principaux idéologues de la Révolution culturelle, dont la veuve de Mao, Jiang Qing.

Octobre 1980: Procès de la «Bande des quatre». Jiang Qing est condamnée à mort et graciée.