The use of ink versus oil

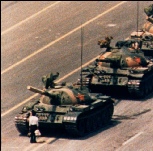

I’m coming back to one of my favorite subjects about Chinese contemporary art. The NON use of traditional techniques by the contemporary artists. It seems that using it will mean not be contemporary.

The reality is that China has a history, and in his history INK is the first technique in painting, technique by the way unique in the world, because there not existed in the WEST.

We cannot go against hundreds of years of history, we cannot renounce to our sources. Use ink will be a logical evolution of the own identity. It is possible to express the ideas through ink, sure that oil or acrylic offer wider possibilities, but they are an influence of the West, not an evolution of the own sources. No other painters can drink from this unique sources.

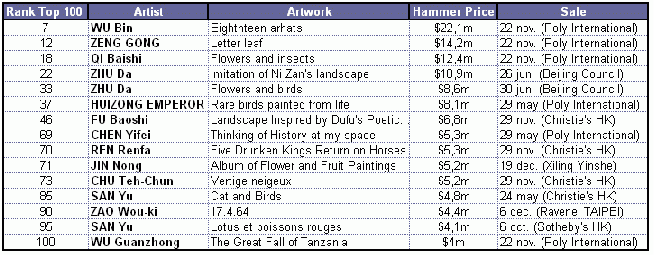

People still appreciates classical ink paintings, and if auctions are a thermometer of this likes, ink is coming back for the first time to the top prices, whenever the contemporary artists almost disappear. In fact, by revenue the first contemporary is Zeng Fanzhi 73 from 35 one year ago, Zhang Xiaogang 129 (29), Zhou Chunya 131 (92) or Yue Minjun 153 (44).

That became logical, as modern painters in west are more valued than contemporary ones, in China was the contrary.

Seeing the works made by the above with ink in the Sanya Collection I’m sure that they are able to make great works, maybe greater than the ones made by modern Chinese artists. That because sure they will add to the technique the thoughts of contemporary people and break from classical issues like flowers, mountains…

Maybe the results of auctions below will open the mind of the contemporary artists that they thought they believe are already open.

China advances [Mar 10] by Artprice.com

The world’s third largest art auction marketplace, China has posted exceptionally dynamic results even during its economic deceleration. And yet at the start of 2009, the meltdown of Contemporary art prices and the success of the Pierre Bergé/Yves Saint Laurent sale in Paris ($265m from Fine Art) suggested that China would be relegated to 4th position behind France.

Not so; in fact the Chinese market continued to flourish in 2009, and while the rest of the world's principal art markets contracted, China’s posted substantial growth. Its annual revenue from Fine Art ($830m) in 2009 represented 17.33% of the global market versus 7.83% in 2008. The three leading auction houses – Poly International, China Guardian and Beijing Council – produced half of that total (almost $400m) and the Hong Kong branches of Christie’s and Sotheby’s generated $200m.

To attenuate the losses stemming from the contraction of top-end Contemporary art prices (which had experienced explosive inflation between 2004 and 2008), the auction houses restricted their offer and moved rapidly into other price brackets and segments. In fact, they managed to sell just as many Contemporary art works as they did during the boom years by offering less speculative names and refocusing their top-end offer onto Modern art and above all Old Masters, generating new world records right in the middle of the global market’s malaise.

This winning strategy allowed 15 Chinese hammer price – including one contemporary – to join the TOP 100 of the world’s best-ever auction results.